Sharing our expertise through pioneering improvement work

The Impact of the Adoption Register

The safety net for children needing to be adopted is being taken away - who will catch them when they fall?

Analysis has shown that there is a national shortage of adopters with a 7% decline in the number of people approved as adopters, according to a 2018 data recently published by the Adoption Leadership Board. Despite a rise in the number of children taken into care, the sector is facing an ever-growing gap between the number of children waiting and available adopters. It is against this unfortunate backdrop that the Adoption Register will be closing on 29 March 2019.

The Adoption Register for England is a national, secure database accessible to all practitioners and adopters who can search the Register for potential matches. The Register has found matches for over 3,200 children in the 14 years since it was established. In recent years it has been responsible for 5% of all children matched for adoption and 15% of children matched with Voluntary Adoption Agency (VAA) adopters.

It is the government’s view that the closure of the Register will have a minimal impact on the sector but closer investigation has revealed a significant potential human and financial cost. As it stands, with the loss of the Register as many as 200 children a year could end up remaining in care rather than being adopted, and local authorities (LAs) would spend around an extra £7.3m per year on supporting those children. In order to cover its annual cost the Register needs to help find adoptive families for two children who would otherwise have remained in care for the rest of their childhood, a target that has been achieved every year since it was created.

The legacy of the Register

The Register received its first referral in December 2004 and in the intervening years more than 25,000 children have been referred and given a greater chance of a life outside of care. Over 80% of these children were classified as ‘harder to place’, by being part of a sibling group, of a black or minority ethnic background, aged 5 and over, or having a disability.

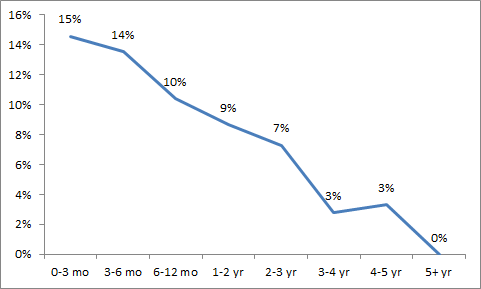

If an LA is not already pursuing a possible match for a child they are required to refer a child to the Adoption Register within 3 months of the Agency Decision Maker approving the plan of adoption, so long as the court has also granted permission or a Placement Order (PO) is granted. The sooner a child is referred to the Register, the higher the chance that a family will be found, as shown in the chart below.

Figure 1: The proportion of children matched by the Register based on how quickly they are referred to the Register following ADM decision

The chances were similar regardless of whether a child was ‘harder to place’ or not, and during the 14 years it has been in operation, the Register has found adoptive families for 13% of the children referred. For most of the remaining 87%, matches will have been found by other means. To maximise children’s chances in adoption, it is vital for social workers to have a number of different family finding tools at their disposal..

The Register has had an important impact, accounting for 5% of all the adoptive matches made in England between 1 January 2015 and 30 September 2018[1], equating to around a fifth of all inter-agency placements made during this period. By comparison the highest contribution by a local authority (LA) or voluntary adoption agency (VAA) over the same period was 3%.

Over 50% of the matches made through the Register were approved within 6 months of the child being referred, and almost 9 out of 10 matches were approved within a year. This timescale is dependent on how quickly agencies take forward a suggested match to panel, which in our experience is usually around three months. This suggests that most matches were identified within 9 months of a child being referred to the Register.

The Register has also played a vital role in helping adopters from VAAs find children. Over half (55%) of the children matched through the Register were placed with VAA adopters. National data on the number of children placed with VAA adopters is not published, but the ALB does publish data on the number of families who are matched with a child. However, if we assume that the average sibling group size is 1.3 children then it could be estimated that the Register accounted for 15% of all the children matched with VAA adopters between 2015-2017, a significant proportion of their business that they now risk losing.

The cost of delivering all these benefits was around £9.24m over 14 years. In addition, during that period the Register also found matches for 23 children who were referred at least two years after their ADM had decided that adoption was appropriate and who would be categorised as ‘harder to place’ when they were referred. It is reasonable to assume that for these children, their LAs had exhausted all other avenues of family finding, including Link Maker, and had referred the children to the Register as a last resort. If matches were not found for these children by the Register it is highly likely that they would not have been adopted at all and the cost of the children remaining in care until they were 18 years old would have been around £9.6m. It is clear that the Register has more than paid for itself in view of these 23 cases alone.

Learning from the Register

Nevertheless, it is clear that the Register could have achieved much more had agencies and the Government enabled it to do so. For example, LAs only met the 3-month time-frame for 39% of children they referred to the Register, while taking up to 6 months for a further 31%. This means that for 30% of children referred the chances of finding a match through the Register were a third lower than they could have been. There are a number of reasons for a referral delay that are outside an LA’s control, such as pursuing potential matches that turned out to be unsuitable or securing permission/authority from the court may have taken longer than expected. But we also know that for some children the delay was simply due to the LA itself.

The Register is by no means perfect and alternatives like Link Maker have shown how some functionality could be improved. The restrictions Government placed on the Register and the way it managed the contract, such as the handling of the adopter access pilot, made it difficult for the Register to reach its potential. It is vital that the Government learns from this as part of its current Discovery work. Link Maker, for example, has been able to refine its product in response to customer feedback, while there was no budget available for the Register to do the same.

So what does the future hold?

Without the Register, agencies may pay to use an alternative product, with the total cost to the sector likely to exceed the value of the Register contract. Some agencies may not be able to afford to use a replacement product and try to utilise their own networks to identify matches for their children. This will no doubt create delays for children who are already drifting in the system.

At the end of its Discovery work on how technology can support family finding in adoption and fostering, the Government may decide that a Register is needed again. It would be an enormous waste of time and resources to build such a database again. One option would be for the Government itself to manage one centralised list of children and adopters available for matching and then allow the market to freely develop applications that access this data and provide social workers and adopters with different ways of searching and identifying possible matches.

A scenario of multiple lists of children and adopters, none of which are comprehensive, should be avoided at all costs. Incomplete lists will lead to missed opportunities for matching. In addition, the lack of a single comprehensive list of children and adopters waiting at any one time would make it impossible to have a clear, real-time picture of the state of the adoption system. The current shortfall in adopters was only predicted as a result of the insight that the Register offers. Agencies also use data from the Register as evidence in court when applying for a placement order. If organisations like Social Care Network, who provide the current CHARMS platform for the Register, and Link Maker are able to build applications that can securely access, process and present Government-held data in the best way they see fit, then adoption agencies will benefit from having a variety of technological means of finding possible matches.

I will continue to analyse the data that is published and report on it to ensure that the impact of the Register’s closure is understood. Unfortunately, it seems likely that in 2019/20 it will take longer to find an inter-agency match for children (as early family finding will only be possible locally) and an increase in the number of POs being revoked as a result of the loss of the Register. The ongoing shortage of adopters will also play a part in this. The next challenge is to look at whether the chances of a child being matched changes significantly after March 2019.

Kevin Yong

References:

[1] based on data published by the Adoption Leadership Board (ALB), http://www.cvaa.org.uk/asglb/data-on-adoption/, using data on matches from 1 April 2014 to 30 September 2018

You may also be interested in:

Adoption data and Collective Matching

Analysis of Ofsted’s annual fostering data collection 2017/18